In the chicken-or-egg conundrum, there’s a third possibility that’s rarely debated: that neither came first — they evolved separately.

That’s essentially the theory put forth by writer/climber Mark Synnott to explain the phenomenon behind Alex Honnold’s stunning 2018 ascent, sans protection, of Yosemite National Park’s El Capitan, and the equally stunning film “Free Solo” that documents the achievement. Would Honnold have attempted such an audacious feat, pushing the bounds of modern climbing to an unheard-of level were widespread public exposure not a possibility? Conversely, would the cameras have been present had climbing not been pushed to the outer limits? Climbing the world’s most challenging routes without a rope? Who does that?

“I don’t think the fact that telling stories while on expeditions has fundamentally changed the sport,” says Synnott, who has written a book on the climb and the climbing revolution leading up to it, “The Impossible Climb: Alex Honnold, El Capitan and the Climbing Life.” Synnott will be on hand to introduce “Free Solo” at a screening Aug. 9 at the N.C. Museum of Art.

Part of the fascination with Honnold’s climb is that it was so viscerally captured on film, by the husband-wife filmmaking team of Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin. The resulting 1 hour, 36-minute film has won widespread acclaim, capturing a bevy of awards including the Academy Award for Best Documentary. Part of the magic of “Free Solo” is that even though you know the outcome, that the film has a happy ending, it maintains an edge-of-the-seat tension throughout.

It wasn’t so long ago that even the most significant achievements in climbing took a while to become public knowledge. When Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay became the first to summit Mount Everest, it was days before they reached a phone to get the word out. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, when new routes and first ascents were popping up in Yosemite and elsewhere, word was slow to get out: “spraying,” or boasting of your achievements, was frowned upon in climbing circles. It could take months before an article eventually appeared in “Climbing,” “Rock and Ice,” or one the climbing world’s other prominent magazines.

Then along came the internet. Synnott, who had been climbing for about a decade and was becoming an elite climber in his own right when the worldwide web began to emerge, was firmly in its cross-hairs, perfectly situated to become one of the pioneers of real-time expedition reporting. The addition of filing media reports on top of the rigors of climbing made it a tempestuous and challenging time to be a climber. And laid the groundwork for Synnott to write about perhaps the most compelling human achievement story of our time.

“I was in a unique position to tell Alex’s story,” Synnott says.

A Crazy Kid Climber is born

Mark Synnott was a typical kid growing up in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, typical in that he did a lot of stuff in his neighborhood and the surrounding woods that his parents didn’t know about. He got his friends involved as well, going so far as to create a secret society, Crazy Kids of America, which awarded prizes for certain feats — like pole vaulting across an icy river. When he was a little older he discovered a 500-foot cliff, Cathedral Ledge, in a neighboring town. His climbing career was launched.

His specialty eventually became first ascents of big walls, which in 1996 earned him a spot on The North Face Climbing Team, a collection of some of the world’s top climbers. It was on one of the first expeditions he led, to Borneo, that he met Alex Honnold. It was an inauspicious start to their relationship.

Honnold wasn’t Synnott’s first choice for the team, but The North Face Climbing Team Director Conrad Anker thought Honnold a good fit. The North Face was going to film the expedition, and Anker pictured it as having a “Young and Old” theme, with the upstart Honnold learning at the feet of old-timers such as Synnott.

“Just like that,” Synnott writes, “I was the old guy.”

Problem was, Honnold really didn’t care what the old guard thought, irritating both Synnott and filmmaker and accomplished climber Jimmy Chin — both of whom would later play key roles in documenting Honnold’s El Capitan feat.

Near the end of the Borneo expedition Synnott quotes Chin as saying “Well, I can tell you one thing. I’m never working with him again.”“The guy was a cocky, elitist son-of-a-bitch,” writes Synnott, “and his failure to acknowledge that he might have learned something from the silverbacks was downright offensive.” It was understandable that they didn’t like the brash youngster who exhibited little respect for this climbing elders.

“But then,” writes Synnott, “why did we still like the guy?”

Climbing, meet the internet

In addition to being in on the ground floor with Honnold and his breaking of the free solo boundaries, Synnott was also in on the ground floor of another big development that would impact the future of climbing: the dawn of the internet.

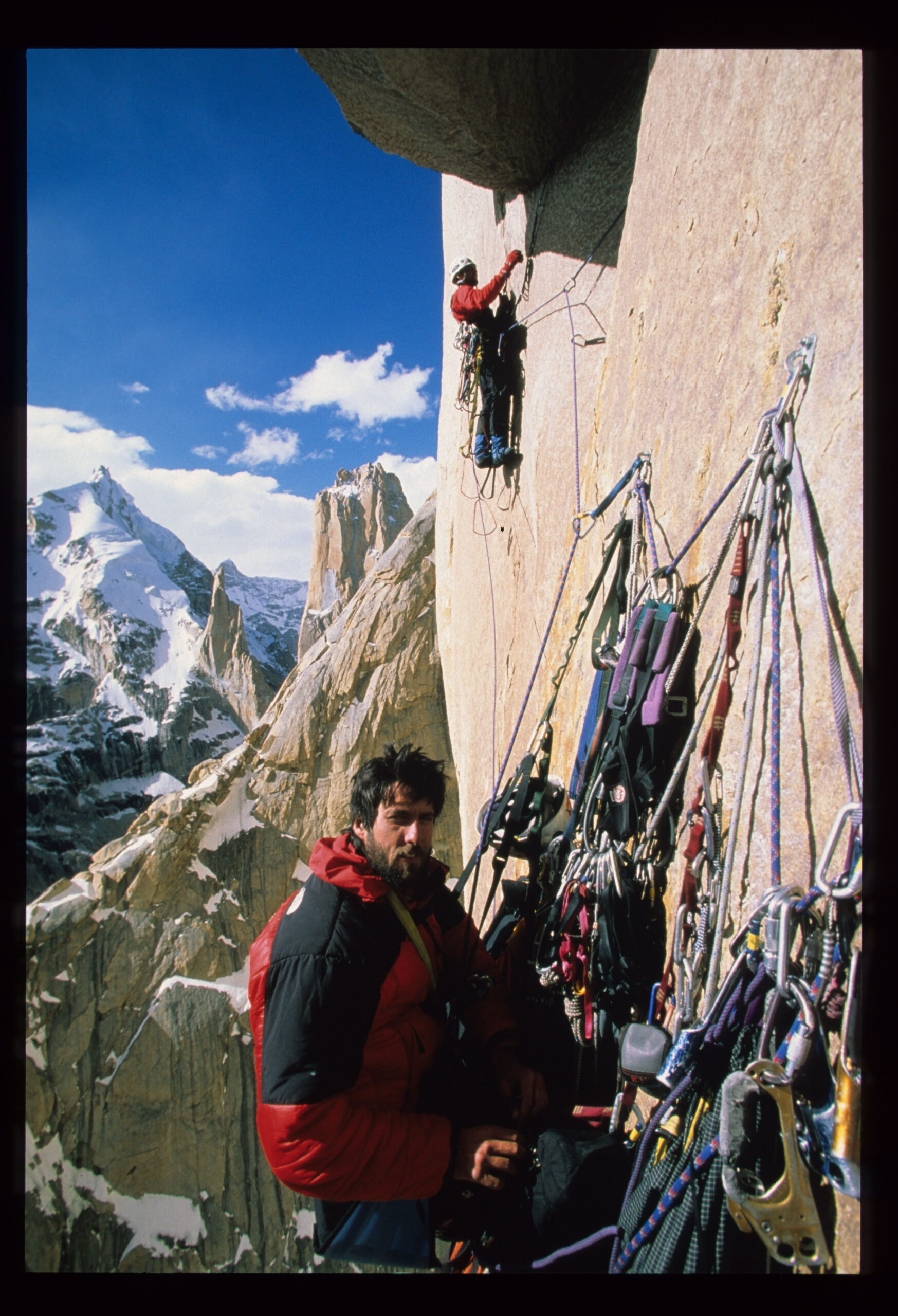

In 1999, Synnott and fellow climbers Alex Lowe and Jared Ogden went to climb the Great Trango Tower, a 4,400-foot wall in the Karakoram Mountains of Pakistan. This expedition would be a little different, however: it would be carried live on the internet by a startup website called Quokka. As a media event for the fledgling internet, the trip proved a success; as a climbing experience it was a disaster. Illness and the demands of filing daily dispatches took its toll on the morale of the team — a morale problem that Quokka quickly capitalized on to boost clicks. But for the fact that Quokka had already sunk $50,000 into the project and the company’s pending IPO depended upon the success of the expedition, the climbers — at least Synnott and Ogden, might have pulled the plug. Climbing is supposed to be about finding your groove, about being a Zen experience, and that wasn’t happening on Great Trango, a climb that involved the trio spending their nights on the wall crammed together on a portaledge “the size of a dining room table.” With so much at stake financially, they soldiered on.

Synnott is cautious when discussing the role the internet has played, not just in climbing, but in society in general.

“The internet, social media — it’s unstoppable force has sort of taken on a life of its own,” Synnott said by phone from the office of his Synnott Guides climbing school in New Hampshire. “What the internet is today, I think back to its genesis, how it’s been driven by markets, by money, by what the world revolves around, and once that Pandora’s box was opened it was inevitable that it was headed in the direction it has to this day.”

But has it been responsible for the direction that climbing has gone, pushing climbers such as Honnold to test the limits of what was once deemed possible — and safe — in a quest for the next big, and marketable, thing?

“I don’t think the fact that telling stories while on expeditions has fundamentally changed the sport,” says Synnott. “Alex is a true, blue, soul brother, a climber to the core. How do external pressures affect him and others? Are they doing this purely for accolades and recognition?”

Driven by the heart

That question is answered both in Synnott’s book and in the film. The bulk of both isn’t about the climb itself, but rather the preparation and events leading up to the climb. Honnold had contemplated free soloing El Cap for years. He also went over every inch of the route he would take, scouting each hold — each smear, each crack, each nub — and practicing them repeatedly, with protection, until he was certain of his odds for success (roughly 99.9 percent, he figured; better odds, he would say, than for driving on the freeway without mishap), and meticulously recording his scouting reports in a composition notebook.

While he knew preparation was critical, he also knew he had to be mentally ready. He aborted his first attempt at free-soloing El Capitan in November 2016 claiming he just wasn’t feeling it. He even used the word “scary,” which Synnott says surprised those closest to Honnold..

But then, on the morning of June 3, 2017, he was feeling it. He started up the wall before dawn and finished 3 hours and 56 minutes later, at 9:28 a.m.

So there’s Exhibit A in the case for Honnold, with years of painstaking preparation, being motivated not by endorsement deals and a book contract, but by the the joy of climbing.

Exhibit B occurred at 8:23 a.m. during the climb. The crux of the climb, the part that had everyone holding their breath, came at what is known as the Boulder Problem an extremely difficult move (in climbing circles rated 5.13a, darn near the hardest ranking currently on the scale). Roped in on a practice run only days before, Honnold had slipped. This time, however, sans protection, he executed the move perfectly, after which he looked directly into one of the nearby cameras documenting his climb and flashed a huge grin.

“That smile,” says Synnott. “You see that smile, you stand in the presence of that, it washes over you. I’ve never met a phony yet in climbing. This sport weeds those types out.”

“You can’t go that deep,” Synnott adds, “unless you’re driven by the heart.”

* * *

Free Solo screening

When: Friday, Aug. 9, 8:30 p.m. (gates open at 7 p.m.)

Where: North Carolina Museum of Art, Museum Park, 2110 Blue Ridge Road, Raleigh

Cost: Free for NCMA members and children 6 and under, $7 for nonmembers

Tickets: Go here for tickets.

Also …

Great Outdoor Provision Co. is sponsoring the Free Solo screening. As part of the overall Free Solo evening are two additional events:

VIP Event at Great Outdoor Provision Co.

When: Friday, Aug. 9, 4:30-6 p.m.

Where: Great Outdoor Provision Co. 2017 Cameron St., Raleigh (Cameron Village shopping center)

What: VIP members are welcome to stop by GOPC to meet Mark, have a beer and pick up free swag from The North Face, including Global Climbing Day T Shirts & The North Face Pint Glasses

Benefits: NC Climbing Coalition

Canteens & Cocktails Pre-Screening Social

When: Friday, Aug. 9, 7:30-8:30 p.m.

Where: N.C. Museum of Art,

What: Mark talks about climbing and the film. Triangle Rock Club to be on hand with climbing shoes, harnesses, ropes and other equipment.